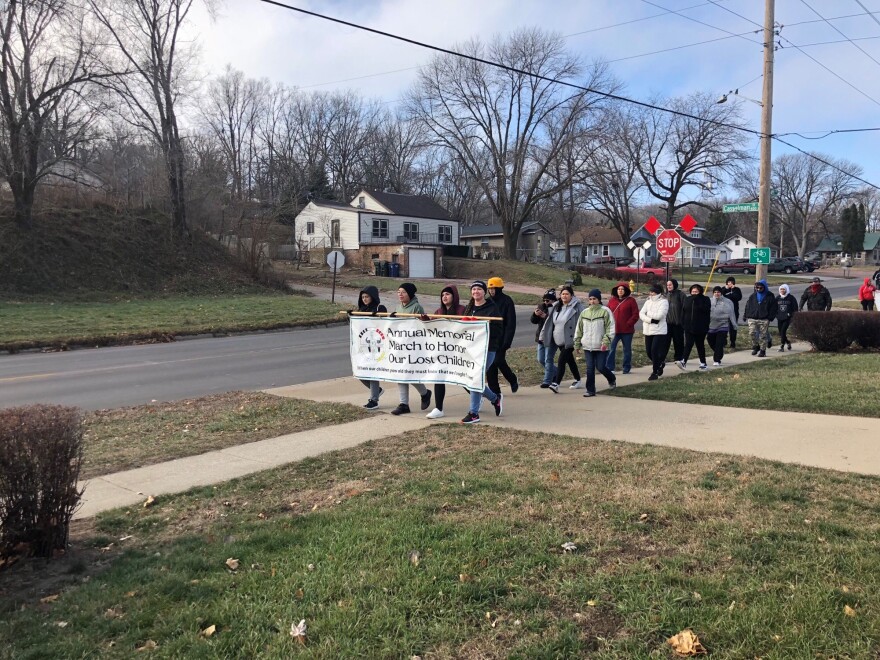

Members of the Native American community journeyed on foot through Sioux City on Wednesday to memorialize Native children who have been removed from their homes and placed in foster care.

To Michael Wanbdigdeski O’Connor, the march is medicine, prayer and healing. He says when he marches, he thinks about the children in the child welfare system who have suffered and others that are suffering.

“These walks over time [have] decreased the division that exists among everybody,” O’Connor said. “And I know that you’ll walk away from here with a better feeling, too.”

In its 16th year, the annual Memorial March to Honor Lost Children helps many seeking community. Native American activist and march organizer Frank LaMere of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska said in a Tuesday interview that at the march’s inception, there was a disproportionate number of Native children in the child welfare system. Often the parental rights of the children's birth parents had been terminated, he said, which is a step toward adoption rather than reunification.

“Nobody heard our complaints, nobody would hear our concerns,” LaMere said. “So the Native community decided we would be counted the only way that they could, and that was with their feet.”

To LaMere, three children in particular come to mind as he marches: Larissa Starr, Nathaniel Saunsoci and Hannah Thomas. These Native children died in foster care, he said.

For years, the Native American community has been at odds with the country’s child welfare system. The federal and state protections in place like the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 and a state version of the law signed in 2003 set standards for foster care when a Native child is removed from their home, but LaMere said he doesn’t feel these laws are fully understood.

"We wish to unify, we wish to heal and we wish to bring our families back together. And this march is a reaffirmation of that." -Frank LaMere

As he stood by War Eagle Monument at sunrise Wednesday morning, LaMere spoke about the hardships families face while parents try to heal from issues like addiction and abuse and their children are separated from them.

“Before the day is out, somebody will say or I will say, ‘Our children feed the system! Our children feed the system! And all of us let it happen.’ And you all think about that. Our children feed the system, we make it easy for them. But that time has to stop.”

He continued, “We wish to unify, we wish to heal and we wish to bring our families back together. And this march is a reaffirmation of that.”

The group walked to different stops in the city to pray for their children, starting at War Eagle Monument, walking to Jackson Recovery Centers and trekking up a hill to reach Siouxland Center for Active Generations. By the time the group reached this stop, more than 120 people were a part of the march.

They ended at the Sioux City Public Museum with a meal, song, prayer and releasing balloons into the air.

It was an empowering day for Crystal Wiemann of the Santi-Sioux Nation, who marched for her three children. She has a 9- and 10-year-old who were removed from her home five years ago and placed with relatives because she was actively using drugs. Wiemann also has a one-year-old who was placed with a non-Native foster family who she said she gets along with very well.

She has been sober for about five months and is working hard to get her children back, she said.

“I attend a lot of therapy,” Wiemann said. “I’m getting ready to bridge from Jackson [Recovery Centers], which means I completed their program. I’m getting ready to get an apartment now.”

Her one-year-old is being returned to her care in mid-December because she met goals set for her by the courts, including getting a job and housing.

“It took me a while to get to a spot where I felt right just going about normal things,” she said.

Wiemann said she feels more efforts should be put into keeping children in their homes.

During a visit to Sioux City on Tuesday, Iowa’s Department of Human Services Director Jerry Foxhoven said DHS is already looking forward to federal legislation passed earlier this year that aims to provide services like mental health and substance abuse treatment to families that need it before conditions get bad enough that their child is pushed into the foster care system.

LaMere said over the years, more work has been done and progress has been made in building bridges between the Native and greater community about child welfare issues. But he says there’s still more work to be done and no Native American children should be taken from their homes.

“We should have no terminations,” LaMere said. “With all the services and supports we have, we should be successful in every case. We are not, in many. We remind [people] of that every year.”