“I shouldn’t tell you this, but she advocates dirty books… Chaucer… Rabelais... BALZAC!” It’s a laugh line that never falls flat, and it advances the plot of The Music Man. Broadway convention meant that Harold Hill and Marian Paroo must end up together, so Meredith Willson needed another dramatic tension, and he found it in priggish opposition to the library. And what bluenoses could be more hilarious - or more believable - than the mayor's wife and her cronies?

But they seem believable only because we don’t know the territory. The Pick-a-Little ladies are not caricatures of their real-life models so much as opposites. In actual Iowa towns of their era, it was women like them who founded public libraries and studied Rabelais and Balzac.

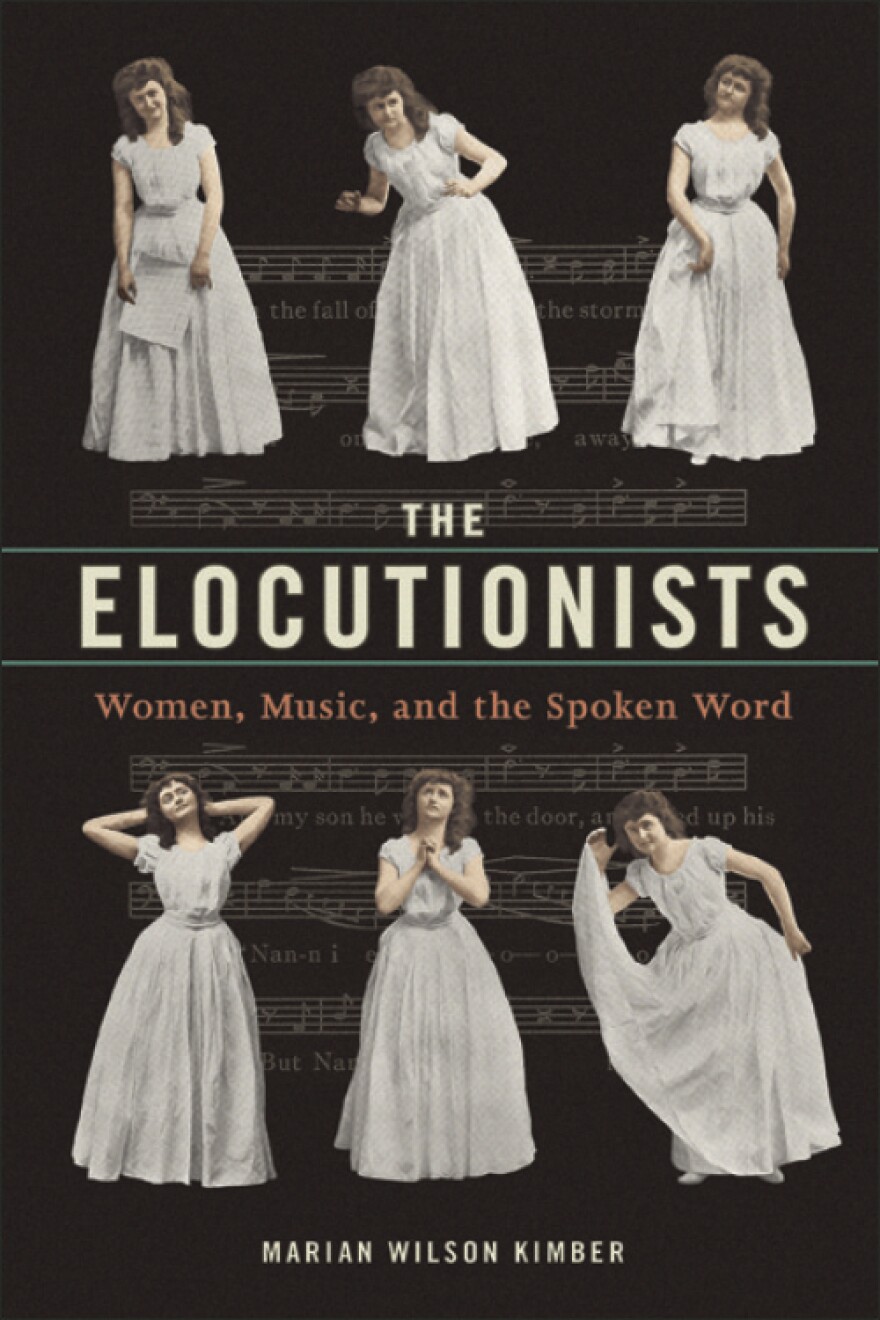

That's one of many striking findings in The Elocutionists: Women, Music, and the Spoken Word, a new book by University of Iowa music professor Marian Wilson Kimber. Not that she picks on Meredith Willson, whose accuracies she also details. Her scope is much larger. She shows that most of us have the same historical blind spot as Willson did, and that it obsures far more than River City. In a number of ways, we underestimate American women of the 1850s-1920s and forget their legacy. We benefit from the institutions they built but ignore their roles in building them. We lampoon the art forms they created but know nothing of the arts themselves. And we don’t begin to grasp how central these endeavors were to shaping American cultural life, and to outcomes we take for granted, like women being welcome to speak outside the domestic sphere.

Wilson Kimber’s writing is as engaging as it is meticulous, her research rich and nuanced but clear as a bell. The book covers a wide range and geography, because the practice of “elocution” was so popular and widespread. My short e-interview with Wilson Kimber cannot do the book justice. I didn’t go into the roots of elocution in an educational system that focused on recitation, for example, or ask about chapters on dialect, the concept of the musical work, and Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream music in performance. But we cover a lot, including Chautauquas, Hoyt Sherman Place, the novelist Ruth Suckow, the Marx Brothers, Sir Patrick Stewart, and Hamilton. And Delsarte posing. That's what Harold Hill was talking the "Pick-a-Little" ladies into, right before they sing that song. Their attempt at posing later in the play brings another reliable laugh, so I found it remarkable to learn that Delsarte was once seen as progressive.

Anyone interested in Iowa and American cultural history should read the book, and also check out the Elocutionists blog. And if Wilson Kimber happens to come to a town near you, don’t miss her. (She will be at the Public Library in Washington, Iowa at noon on Thursday, June 14th.) She doesn’t only talk about The Elocutionists, she also performs their work, something few musicologists would dare. I ask her how she started below (and also include a youtube clip!). Here's our interview:

________________________________________________________________

What was “elocution”?

Elocution was the art of using speech to interpret the meaning of a text.

How was that different from, say, voicing a script in radio or television today, when we try to sound conversational even when we read from a text?

Today, we think of speech as “natural,” but elocutionists were trained in a stylized, almost musical style of reciting. Elocution was considered more complicated than singing, since singers already had predetermined pitches but elocutionists had to make them up themselves.

When did “elocution” emerge as a genre, and how big a role did it play in American culture?

A major role! Elocution became a popular activity beginning in the nineteenth century, and not only in the USA: if you read Anne of Green Gables (which is set in Canada) or saw the PBS adaptation, you might recall how much Anne enjoys elocution, reciting poetry in public concerts. Her activities were typical. Here in the US, if you look at century-old concert programs, you discover that it used to be a normal expectation to encounter poetry or monologues between musical numbers. Many compositions for spoken word with accompaniment were written for the elocutionists who performed across America into the early twentieth century.

Even before the nineteenth century, men who aspired to careers as politicians, attorneys, or preachers studied elocution, partly to learn to project their voices without amplification.

ELOCUTION AND GENDER

That brings up a central thread of the book: the ways in which elocution was related to gender. To start, you show that men’s oratory took place in the public sphere in positions of power, like politics, law, or the ministry, but that women were supposed to recite only in the domestic sphere. Elocution, you say, provided a bridge that let women who weren’t Queen Victoria speak outside the home while remaining “respectable.” How did this progress in the US?

Reciting to entertain your family at home was socially acceptable. Then, in the late nineteenth century, the rise of women’s clubs provided places outside the home for women to recite. Women were able to appear in public because they were transmitting “great literature,” not giving political speeches or appearing as morally “questionable” actresses. Many received training at the oratory schools in every major American city. By 1892, when the National Association of Elocutionists had its first meeting, three-quarters of the attendees were women.

You write about how elocution came to be “gendered,” seen as a woman’s activity. You also describe how it was satirized, and you argue that this in part reflected a broader “cultural denigration of female artistic endeavor.”

Most of the negative reaction came from men who were unhappy that women had successfully taken over what had been a male profession. Female performers were critiqued as amateurish or overly sentimental. Elocution was almost too popular—one writer called it a “distemper!”

CHAUTAUQUAS, RUTH SUCKOW, AND WHAT THE MUSIC MAN GOT WRONG

As an Iowa Public Radio host, I was taken by how often your book treats the history of these arts in Iowa. Did you start out intending to research local history?

No, but I couldn’t escape it! My job interview at the University of Iowa was the first time I ever heard the word “Chautauqua.” I only learned later that in the 1910s and 1920s, the summer Chautauqua tent circuit provided music and spoken word performances to the Midwest’s rural audiences, and that one of the major talent agencies was in Cedar Rapids.

Stuffed in a scrapbook at Curry College in Milton, Massachusetts—a former elocution school—I found a photocopy of chapters from a 1926 novel, The Odyssey of a Nice Girl. This novel, about a girl who goes to elocution school, turned out to be by Ruth Suckow, who was born in Hawarden, Iowa, attended Grinnell, and then Curry. She spent much of her adulthood in Cedar Falls. She ended up being the focus of my first chapter.

Another chapter every Iowan needs to read right now is on Delsarte posing in Iowa, which most of us know only from the satirical treatment of the “Grecian Urn” ladies in The Music Man. So I was surprised to learn that Delsarte was once considered progressive.

In Delsarte, women in white gowns posed as Greek statues or expressed literary content in physical poses. Delsarte made a good finale for an evening of music and elocution, but it also allowed women to abandon their corsets and move freely. You might think of it as similar to today’s yoga, both physically and mentally “good for you.” I was dubious about this, until I convinced my music history class to try Delsarte and discovered that it actually does feel good.

You argue that The Music Man radically misrepresents the Mayor’s wife and her circle. It portrays them as “ignorantly opposed to high culture,” but in real Iowa towns these women were exactly the people who would be studying Balzac and Rabelais, not the ones being outraged by them. You show that these women in fact made huge and lasting contributions to our cultural life. Who were they?

The women in Iowa’s clubs were amazing! They were a major force in working to improve their towns through contributing to their public libraries or performing at music clubs. The ladies of Marshalltown’s Hawthorne Club were studying Wagner’s Parsifal in 1905. Iowa women created cultural institutions that endured, such as Hoyt Sherman Place, built by the Des Moines Women’s Club. With a grant from the State Historical Society of Iowa, I’m still researching our clubwomen, focusing on how they promoted the state’s composers in the 1920s and 1930s, even in smaller towns, like Tama and Greene.

I can’t wait to hear what you find! A broader point of the book is that these women were central, not peripheral, to the overall history of classical music and its institutions. I’d never seen them treated that way in standard music histories.

Classical music is obsessed with oversized male personalities, overshadowing the people who make their careers possible. Women arts patrons are often treated with ridicule—think of the character Margaret Dumont played in the Marx Brothers’ movies. Another factor is that historians sometimes don’t recognize that musical life takes place everywhere, not just in large urban areas. When I showed an Iowa map with many dots indicating where Delsarte took place at a musicology conference, you could literally hear the room gasp!

ELOCUTION, WOMEN COMPOSERS, AND REVIVING LOST WORKS (SOME OF THEM PRESERVED IN A LAUNDRY BASKET)

Let’s return to the art of the elocutionists. How did elocution come to combine spoken words with music?

Since elocutionists performed at concerts, it was easy to add music. Poetry could be given with piano accompaniments, and songs could be spoken rather than sung. If a poem mentioned a well-known hymn or song, it could be played at that point. One reason we don’t remember this took place is that nothing was written down, so I’ve had to reconstruct these practices.

That is such a contrast to how we think of that era’s classical music, with its focus on fully written-out works. How did elocution with music affect women who were composers?

Because women were elocutionists, women composers in the twentieth century also took up creating works that could be performed for women’s club audiences. Two female composers performed pieces for spoken word and piano for decades, Frieda Peycke in Los Angeles, and Phyllis Fergus in Chicago. Both had been completely forgotten. Fergus’s daughters literally brought a laundry basket of her music out of the basement to show me.

Recently you’ve taken up performing these women’s compositions. Why did you decide to try elocution yourself?

Both Fergus and Peycke received great reviews. I found their pieces clever and charming and thought, “somebody really needs to perform these.” I finally had to admit that the best person to attempt this was me! My wonderful pianist, Natalie Landowski, helped me to figure out how to make the combination of music and speech work. We’re on our tenth concert now—people still enjoy these pieces, mostly because so many of them are very funny. [BELOW: Marian reciting Frieda Peycke's If Only We Could.]

ELOCUTION AND THE FATE OF WOMEN’S ARTS

Let me move to another implication you explore: that an art form can thrive widely yet disappear completely. What caused the demise of elocution?

To put it simply, the world changed. The kinds of Victorian poetry elocutionists performed were no longer popular. At the same time that there was a backlash against women’s success in elocution, it also became more socially acceptable for women to enter theatrical life. The rise of radio and movies made other entertainments available.

Today we’re used to prophecies of artistic doom that don’t come to pass—the death of the novel, of classical music, of radio. But so far, the novel and classical music have thrived, and radio listenership has increased. Based on your work, should we be more worried?

After learning about the disappearance of elocution, I do tend to worry more when I read those dire forecasts! What I’d like to emphasize is that it is art forms by women that are usually in more danger. Many classical ensembles are currently working to program more compositions by women. In the era of elocutionists, women composers’ works were heard far more frequently than they are today. So it’s not only difficult for women to get their art forms before the public, it’s harder for them to stay there in the long term.

Did the combination of elocution and music have any lasting impact?

Since we’ve lost the more stylized versions of elocution, most of the spoken word compositions popular a century ago are not performed today. A few years ago Sir Patrick Stewart and the pianist Emanuel Ax recorded Richard Strauss’s setting of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Enoch Arden, one of the most substantial of these works. In another sense, although it’s not the same style as elocutionists performed, the combination of speech and music continues to be all around us—in the movies, on television, or in Hamilton.

Or Kendrick Lamar, right? But did the works of the elocutionists last at all?

I usually say that the compositions by women were completely forgotten. But one of Phyllis Fergus’s pieces, The Usual Way, satirizing marriage, was a regular feature of bridal showers for years. I’ve found it being performed as late as 1976 in Milford, Iowa. And the lady who invited me to perform at the Washington, Iowa, Public Library told me she used to perform Fergus’s Soap, the Oppressor, when she was a little girl. Women’s arts are there, if you are willing to look.

________________________________